There is a general belief among film critics that if it makes us laugh, then it is not to be taken seriously. Drama and comedy are often thought of as being like night and day, yin and yang. One makes us laugh, the other makes us feel and/or think. But isn’t laughter one of the most fundamentally human expressions there is? Doesn't it therefore warrant our inquiry? Understanding humor can not only tell us something about what it means to be human, but also, what it means to belong to a certain culture at a particular time and place. So why is there this distinction between “serious” films and comedies in terms of the critical and scholarly attention that they receive?

There is a general belief among film critics that if it makes us laugh, then it is not to be taken seriously. Drama and comedy are often thought of as being like night and day, yin and yang. One makes us laugh, the other makes us feel and/or think. But isn’t laughter one of the most fundamentally human expressions there is? Doesn't it therefore warrant our inquiry? Understanding humor can not only tell us something about what it means to be human, but also, what it means to belong to a certain culture at a particular time and place. So why is there this distinction between “serious” films and comedies in terms of the critical and scholarly attention that they receive?

Perhaps it is all just a conspiracy to prevent Adam Sandler from ever winning an Academy Award. I am joking, but as with most jokes, my comment contains an element of truth. The fact is that comedies (even really good ones) very rarely win Academy Awards or any other critical accolades. People don’t think about comedies; they just laugh at them.

Despite this, some of the most popular American films of all time have been comedies, and every year, at least one comedy makes the top ten in terms of box office figures, often several. Also, from a production point-of-view, they tend to be a pretty good return on investment, as they do not usually cost much to make and often do quite well in terms of domestic box office receipts.

So why don’t we study comedies with the same depth of analysis that we do with their dramatic counterparts? Why can’t we talk about Airplane! or Blazing Saddles in the same way that we discuss Citizen Kane or The Godfather? (Hint: we can.) This is one of the main points that I hope to address in this class: comedies deserve the same level of respect and depth of scholarship as any other kind of film, and through such analysis, they can yield just as much insight into the social landscapes from which they emerged and were received as other movies, arguably even more so.

After all, consider for a moment how much you can tell about a person by his or her sense or humor. Think about how many of your friends are your friends precisely because you laugh at the same things (and therefore may also share similar ideologies). A line from a movie can be like a secret handshake. Now apply that same idea to a segment of American culture at a specific moment in our history. Popular comedic films serve as historical records of what people thought was funny, and knowing why a movie resonated with a mass audience can tell us a great deal about that audience. In short, by analyzing the humor in a popular comedic film, as well as its narrative structure and thematic content, we can learn a lot about the dominant anxieties within the culture that served to make this movie successful in the first place. Pretty interesting, right?

After all, consider for a moment how much you can tell about a person by his or her sense or humor. Think about how many of your friends are your friends precisely because you laugh at the same things (and therefore may also share similar ideologies). A line from a movie can be like a secret handshake. Now apply that same idea to a segment of American culture at a specific moment in our history. Popular comedic films serve as historical records of what people thought was funny, and knowing why a movie resonated with a mass audience can tell us a great deal about that audience. In short, by analyzing the humor in a popular comedic film, as well as its narrative structure and thematic content, we can learn a lot about the dominant anxieties within the culture that served to make this movie successful in the first place. Pretty interesting, right?

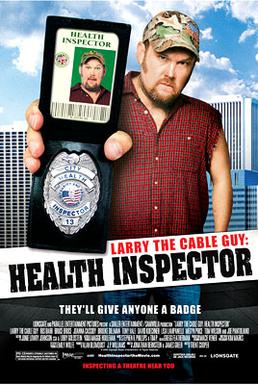

But what is a comedy? Is it a genre? Is it a mode? What about movies that are generally serious but include moments of comic relief to break the dramatic tension? Take Billy Wilder's The Apartment, for example. (Seriously, watch it. It’s a very good movie.) And what about movies that are meant to be funny but aren’t — like Jack and Jill or Larry the Cable Guy, Health Inspector? (Which is it Larry, are you a cable guy or a health inspector? Yes, even the title is stupid.) This brings me to another point: Isn’t our sense of what is or isn’t comedy entirely subjective? So how do we study something that means one thing to one person and another thing to someone else? (And if I use any more parentheses in this paragraph, it’s going to look like a compilation album of eighties rock ballads.)

Let’s start with genre. From an industry perspective, genre is primarily just a marketing tool, a way that studios can let audiences know whether or not they may like a certain movie. Back in the days of video stores, genre was the category where you would find a certain movie; today, it’s broken down into even more specific sub-genres on your Netflix queue, but it’s the same basic idea. Comedy is a broad category through which films are marketed to their potential audiences.

That said, it seems that the only objective way to address the issue of whether a film is a comedy or not is to determine if a movie was marketed by its studio as such. This way, we can avoid any subjective judgments of taste and just see if a movie is listed on IMDB as a comedy. If so, then we can assume that this is how the studios wanted it to find an audience, so whether or not we think it is funny, we can therefore consider it a comedy. Beyond this, although there is no definite criteria, it seems that generally speaking, if the primary purpose of a film is to make us laugh, then it is probably in fact a comedy.

That said, it seems that the only objective way to address the issue of whether a film is a comedy or not is to determine if a movie was marketed by its studio as such. This way, we can avoid any subjective judgments of taste and just see if a movie is listed on IMDB as a comedy. If so, then we can assume that this is how the studios wanted it to find an audience, so whether or not we think it is funny, we can therefore consider it a comedy. Beyond this, although there is no definite criteria, it seems that generally speaking, if the primary purpose of a film is to make us laugh, then it is probably in fact a comedy.

But can't a movie also make us think while it makes us laugh? This may even be the most effective way to influence the way an audience thinks, by sneaking in ideology under their noses while they're distracted by laughter. Watch a George Carlin routine on YouTube. He wasn't just making people laugh; he was changing the way people looked at the things that were most familiar to them.

We will consider ideas such as this throughout the semester, and a lot of our analyses will focus on the thematic and ideological content of these films as well as the targets of the jokes within them. What were the filmmakers really trying to say and how were they going about making us laugh?

Comedy, it can be argued, is always political. By that, I mean that when you laugh at a joke, you consent to a certain alignment of perspectives between yourself and the teller of the joke. This inherently creates inside and outside groups (people who laugh at the joke and those who don’t) who are often connected by a common ideology, and the very act of getting a joke involves a synthesis of two dissimilar ideas that leads to a new understanding. Our laughter results from the resolution of an intellectual incongruity.

In other words, the basic formula for a joke is: familiar context + introduction of an unexpected element = new way of seeing the familiar.

In sometimes very subtle and nuanced ways, comedy shows us new ways of seeing what we think we already know, and it thus has the power to change the way people understand their reality. Comedy undermines some of the basic assumptions that people take for granted, and this can be a precursor to actual societal change. For better or worse, laughing at something can be a way of taking away its power. This can be used to marginalize, as in racist and sexist humor, but it can also be used to fight social injustices and better align our collective ideals with reality.

In sometimes very subtle and nuanced ways, comedy shows us new ways of seeing what we think we already know, and it thus has the power to change the way people understand their reality. Comedy undermines some of the basic assumptions that people take for granted, and this can be a precursor to actual societal change. For better or worse, laughing at something can be a way of taking away its power. This can be used to marginalize, as in racist and sexist humor, but it can also be used to fight social injustices and better align our collective ideals with reality.

As we will see throughout this semester, comedic films sometimes have very substantial things to say about some of the most serious issues of the day. Consider Charlie Chaplin’s City Lights. At its core, it is a story about the dynamics of inter-class relationships during the Great Depression. Sounds hilarious, right? It actually is quite funny, and looking deeper into its subtext doesn’t diminish one’s enjoyment of the film, but rather, it only enhances it. The same can be said for any of the films that we will be watching throughout this semester.

At this point, you’re probably wondering what to expect from an online class about film comedy. Well, for one thing, it might be the only class you’ll ever take in which it’s perfectly acceptable to attend in your pajamas. You’ll also be pleased to know that I have no policy regarding cell phones. If you’re distracted while you’re watching these movies, that’s entirely on you. This is, of course, true with just about any class, but what you get out of this course is highly contingent on how much you put into it.

With this in mind, I have structured this class to have somewhat of a Choose-Your-Own-Adventure type format. That is, on most weeks, you will get to choose between multiple films in terms of which one you want to write about. It is my hope that you will therefore have a movie that you can not only find relatively easily each week, but one that you will enjoy as well. I know it probably sounds crazy, but I am of the belief that people tend to get more out of a class that they actually like.

More information about all of this is in the syllabus, which I emailed to everyone and have uploaded to Canvas. It can also be found here. Please read it over carefully. I'm pretty sure that I can speak for all teachers everywhere when I say that I do not like to answer questions that can be found simply by reading the syllabus. It’s only five pages. This is an upper-level class. You can do it.

I firmly believe that this will be a fun class, and by the end of the semester, you might even be a little surprised at how much you have learned about film, American history, and the basic mechanics of humor. We will also watch some pretty great movies that I think you will enjoy.

Your assignments for Week 1 are:

1. Get the books if you have not done so already. They are not expensive, they are both very interesting, and you might even be able to find used copies online.

2. Read the syllabus. Seriously. It’s only five pages. You’re in college.

3. Look over the assignment chart. Know when it is your turn to write blog posts and note those dates on your own personal calendars. These are due by 6:00 pm on the Sunday at the beginning of that week. Therefore, next week, the following people will be doing blog posts:

1. Get the books if you have not done so already. They are not expensive, they are both very interesting, and you might even be able to find used copies online.

2. Read the syllabus. Seriously. It’s only five pages. You’re in college.

3. Look over the assignment chart. Know when it is your turn to write blog posts and note those dates on your own personal calendars. These are due by 6:00 pm on the Sunday at the beginning of that week. Therefore, next week, the following people will be doing blog posts:

Michael Abels (Mike Judge biography)

Cynthia Baber (Trey Parker and Matt Stone biography)

Katrina Bertz (Review of reviews: Idiocracy)

Samantha Bodette (Review of reviews: Team America)

Email me with any questions, sooner rather than later.

4. Write a short (one or two paragraph) bio about yourself along with your picture and email it to me as soon as possible. I will post these on the blog in the section called “Contributing Authors” so that we can all get to know something about each other. Some of you may even be working together later in the semester.

5. Read Chapters 1-4 of the Misch book. It is a fun, easy read. Don’t be surprised if you end up reading the whole thing in one sitting, or approximately two trips to the bathroom.

6. Watch Sullivan’s Travels (Preston Sturges, 1941). Comedy class or not, this is one of those movies that everybody should watch. I have posted biographical information about Preston Sturges on the blog. This is meant to serve as context for the movie, but also, as a basic example for when it is your turn to write blog posts. Of course, students are more than welcome to take theirs further.

7. Following the guidelines for screening questions that are outlined in the syllabus, for all students except those listed after #3 above, answer the following question and upload your response to Assignments/Screening Question #1 on Canvas by Sunday, January 17 at 6:00 pm:

Based on the assigned reading and your understanding of Sullivan’s Travels, explain what you believe to be the social function of comedy.

No comments:

Post a Comment