As we discussed last week, a director is sometimes thought of as the "author" of a motion picture, even though film, by its nature, is a collaborative medium. As such, it may be better to think of a director as the creative decision-maker whose vision of the film unites the work of all of the other artists and technicians involved. If someone in the cast or crew has a question, it's the director's job to have the answer. Fundamentally, directors solve problems, and they are responsible for the overall cohesion of their films.

Producers, on the other hand, generally handle the business end of making a movie. In television, the role of producer has a different meaning, but in films, it is the producer(s) who hires the director and the rest of the crew. They also secure the rights to intellectual properties and then hire writers to develop them into screenplays (and often hire separate writers to perform rewrites). A producer's job is essentially to put together the people and the resources necessary to make a movie. During production, they oversee its budget, and when the film is complete, they work to ensure that their product is financially successful. To a producer, a movie is, above all else, a commodity in which people have invested large sums of money, and their job is to help that film make a profit. Although they can certainly have creative input in the making of a movie, their role generally centers on the money involved in making and distributing it. If a film does well, the producers tend to get paid pretty well for it, and if it wins an Academy Award for Best Picture, the Oscar goes home with the producer.

According to the Hollywood Reporter, as of 2014, the average American [feature-length narrative] film cost about $40 million to make, not including marketing expenses, which can cost just as much or more than the film itself when distributing it to a global market. Back in 1997, Titanic became the first movie to cost $200 million to produce. (I haven't seen it yet, so don't tell me how it ends.) Since that time, there have been forty-seven other films with production budgets of at least that much. When international distribution is taken into account, every single one of these movies eventually made a profit. Even John Carter. Of course, there are still the marketing expenses, but then there are also other ways that movie generates income, such as product placement and licensing fees. Frankly, studio accounting gets pretty complicated, and that's just the way they like it.

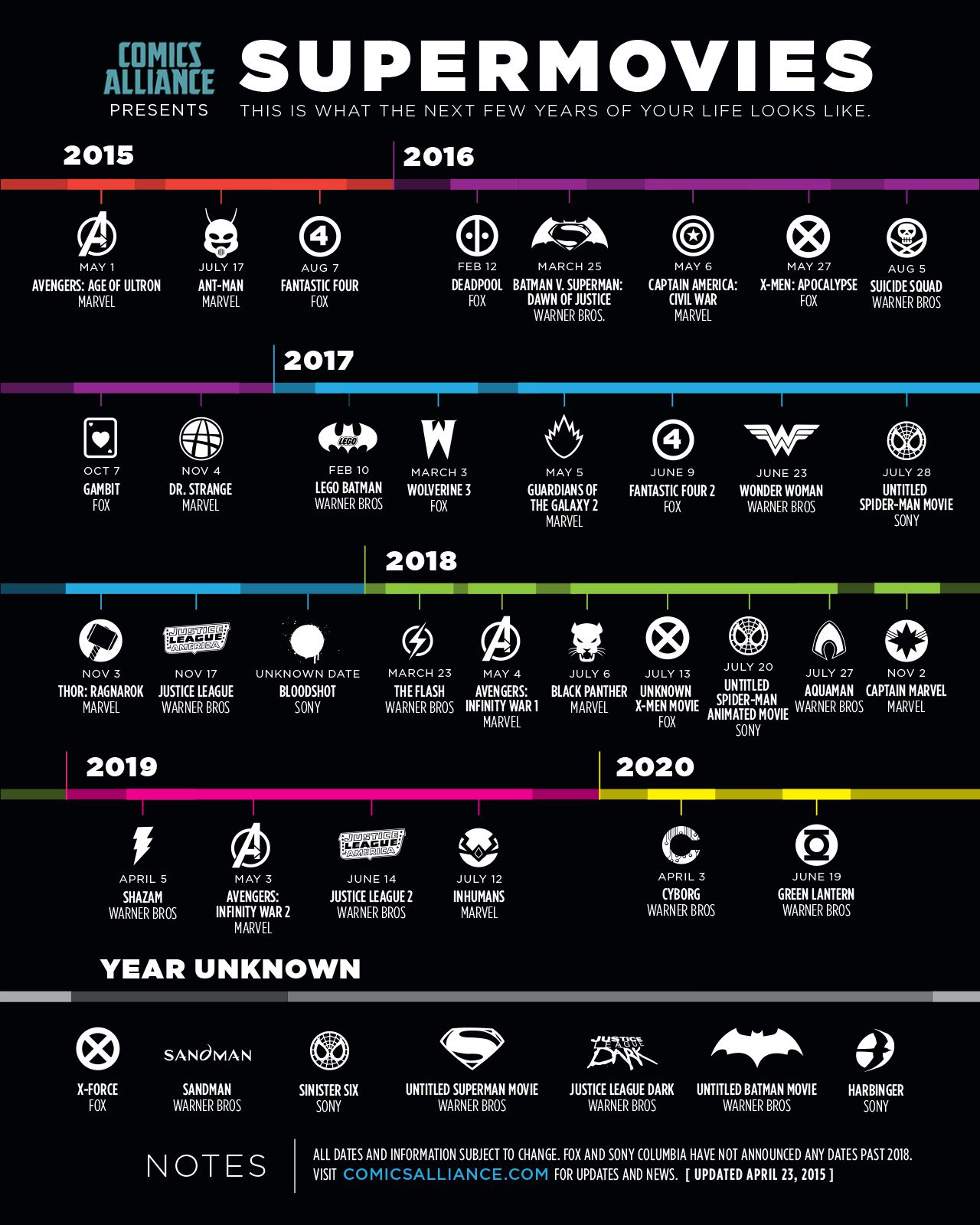

My point is that this is essentially why the industry is what it is today. Big budget movies tend to make money, and domestic distribution only accounts for part of that. Movies today are made with global markets in mind, and the more money these films make, the more likely producers are to keep making them. When film historians look back at this period in cinema history, they will likely refer to it as the era of the franchise film. That is a term for movies that generate endless sequels and spinoffs, and the reason that they are made so often today is that most of the marketing on them is already done. This isn't to say that they don't still have huge marketing expenses, but they're at least selling a familiar concept to their potential audiences. "It's the fourth one of those movies about the ride at Disneyland, starring Johhny Depp doing an impression of Keith Richards!" Audiences already know what to expect. From a producer's perspective, these movies are a safe bet, and there is nothing that investors like more than a safe bet, especially when we're talking about budgets that are bigger than the GDPs of some countries. Seriously.

Take, for example, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, which cost $410 million, not including marketing costs. Think about that for a minute. Four hundred and ten million dollars. I did the math, and that would pay my rent for about thirty-four thousand years. I'm not kidding. It would also buy enough string cheese to reach the moon. When a single movie costs this much to make, there is obviously a lot at stake. And because the trend in Hollywood has been to make fewer movies each year but with increasingly enormous budgets, these costs just keep ballooning. It would only take a few major flops in a row for such a balloon to burst, which could easily end a studio. It has happened before. Today, they're banking on the fact that nobody will get sick of superhero movies at any point in the near future. We'll see how that works out...

Genre, as discussed on week one, can be thought of primarily as a marketing tool. It is a way for audiences to know whether or not they may like a movie. Take superhero movies, for example. They can be thought of as their own separate sub-genre of action movies. In any superhero movie, we know that it will feature someone with extraordinary powers engaged in a battle of good versus evil in which good will ultimately triumph. Particularly in recent years, though, the idea of genre has become somewhat more convoluted, as the immense costs of most Hollywood films today make it so that in order to recoup those costs, they have to appeal to a lot of people. To do so, most of these films are designed to fit comfortably within multiple genres. Don't like science-fiction? Can I interest you in an action movie? How about a romantic subplot? In other words, there is something in it for everybody.

When a movie is thought to belong to a certain genre, though, an audience develops a set of expectations of that film, whether consciously or otherwise. We anticipate that it will adhere to certain conventions. For example, if it is a western, we know that it will most likely feature cowboys and open plains, because these are some of the conventions of this genre. If it is a science-fiction movie, it may have elements of outer space and/or a futuristic setting. If it is a comedy, then it probably features elements of incongruity and exaggeration, and it is fundamentally designed to make its audience laugh. Basically, genre is a way of setting up audience expectations by delivering them with certain conventions from which the film can then build upon. It refers to both form and content.

Satire, as we read about last week, is a specific sub-genre of comedy. It is subversive and it risks being offensive, and it is always, on some level, political. As King notes, satire "offers a way of tackling serious social-political material without slipping into over-insistent and 'preachy' realms of melodrama or straight propaganda" (107). He also says that, "In some cases, however, comedy of a satirical variety may be the only way in which internal social or political criticism can reach an audience" (94). If you'd like to see an example of satire in action, I encourage you to watch this clip of Steven Colbert at the 2006 White House Correspondents Dinner.

They say his testicles grew three sizes that day.

Satire is not safe. For this reason, film producers tend to stay away from it. King talks about how satires usually only get made if they are independently produced or if the content is watered down enough to make them appear harmless. He argues that, "Absurd broad comedy and caricature dilute the satirical impact but also help to enable films such as this to gain finance, distribution and a broader audience than would otherwise be the case. The precise boundary of the substantially satirical is not easy to identify, but it might be suggested by a darker and/or sharper edge in the overall mix" (105). In other words, sometimes elements of satire are interwoven within other, more innocuous forms of comedy and/or hidden in the subtext, but you can usually pick out the satire because it contains an element of sharp social criticism.

All three of last week's movies satirized U.S. politics. Being There offered a satire of "Washington outsiders" at a time when our political system seemed broken; Election was, in many ways, a satire of political corruption in our two-party system; and Wag the Dog offered commentary on the ways in which politicians manipulate the public through mass media. These films could also be thought of as being part of a sub-genre of political comedies, as they all adhere to similar conventions (i.e. they are about American politics, they offer commentary on real-life events through satire, they maintain an aloofness that prevents us from taking them too seriously, etc.).

In a similar respect, all of this week's films are parodies. They are: Hot Fuzz, I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, and Airplane! As you will read about this week, parody differs from satire in some pretty significant ways. Whereas satire offers political or social commentary, parody is a deconstruction of aesthetics. A parody film exposes the conventions of a genre, leaving them open to ridicule. It may also poke fun at a specific work, whether film or otherwise. A parody can contain elements of satire, but it is not a requisite. As I will discuss in more depth next week, parodies have been around for nearly as long as motion pictures have existed, and they essentially serve as inside jokes with their audiences. It can also be argued that parodies prevent film form and content from becoming too predictable because they point out cinematic conventions that have become clichés and should probably be retired.

As you're watching this week's movies, I want you to think about the genres and/or specific films that they are deconstructing. Depending on your familiarity with these types of movies, this may require some additional outside research. Once you have watched at least one of them and read this week's blog posts for context, as well as the assigned reading (King chapter three, second half: pg 107-138), please respond to the following screening question prompt:

Producers, on the other hand, generally handle the business end of making a movie. In television, the role of producer has a different meaning, but in films, it is the producer(s) who hires the director and the rest of the crew. They also secure the rights to intellectual properties and then hire writers to develop them into screenplays (and often hire separate writers to perform rewrites). A producer's job is essentially to put together the people and the resources necessary to make a movie. During production, they oversee its budget, and when the film is complete, they work to ensure that their product is financially successful. To a producer, a movie is, above all else, a commodity in which people have invested large sums of money, and their job is to help that film make a profit. Although they can certainly have creative input in the making of a movie, their role generally centers on the money involved in making and distributing it. If a film does well, the producers tend to get paid pretty well for it, and if it wins an Academy Award for Best Picture, the Oscar goes home with the producer.

According to the Hollywood Reporter, as of 2014, the average American [feature-length narrative] film cost about $40 million to make, not including marketing expenses, which can cost just as much or more than the film itself when distributing it to a global market. Back in 1997, Titanic became the first movie to cost $200 million to produce. (I haven't seen it yet, so don't tell me how it ends.) Since that time, there have been forty-seven other films with production budgets of at least that much. When international distribution is taken into account, every single one of these movies eventually made a profit. Even John Carter. Of course, there are still the marketing expenses, but then there are also other ways that movie generates income, such as product placement and licensing fees. Frankly, studio accounting gets pretty complicated, and that's just the way they like it.

My point is that this is essentially why the industry is what it is today. Big budget movies tend to make money, and domestic distribution only accounts for part of that. Movies today are made with global markets in mind, and the more money these films make, the more likely producers are to keep making them. When film historians look back at this period in cinema history, they will likely refer to it as the era of the franchise film. That is a term for movies that generate endless sequels and spinoffs, and the reason that they are made so often today is that most of the marketing on them is already done. This isn't to say that they don't still have huge marketing expenses, but they're at least selling a familiar concept to their potential audiences. "It's the fourth one of those movies about the ride at Disneyland, starring Johhny Depp doing an impression of Keith Richards!" Audiences already know what to expect. From a producer's perspective, these movies are a safe bet, and there is nothing that investors like more than a safe bet, especially when we're talking about budgets that are bigger than the GDPs of some countries. Seriously.

Take, for example, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, which cost $410 million, not including marketing costs. Think about that for a minute. Four hundred and ten million dollars. I did the math, and that would pay my rent for about thirty-four thousand years. I'm not kidding. It would also buy enough string cheese to reach the moon. When a single movie costs this much to make, there is obviously a lot at stake. And because the trend in Hollywood has been to make fewer movies each year but with increasingly enormous budgets, these costs just keep ballooning. It would only take a few major flops in a row for such a balloon to burst, which could easily end a studio. It has happened before. Today, they're banking on the fact that nobody will get sick of superhero movies at any point in the near future. We'll see how that works out...

Genre, as discussed on week one, can be thought of primarily as a marketing tool. It is a way for audiences to know whether or not they may like a movie. Take superhero movies, for example. They can be thought of as their own separate sub-genre of action movies. In any superhero movie, we know that it will feature someone with extraordinary powers engaged in a battle of good versus evil in which good will ultimately triumph. Particularly in recent years, though, the idea of genre has become somewhat more convoluted, as the immense costs of most Hollywood films today make it so that in order to recoup those costs, they have to appeal to a lot of people. To do so, most of these films are designed to fit comfortably within multiple genres. Don't like science-fiction? Can I interest you in an action movie? How about a romantic subplot? In other words, there is something in it for everybody.

When a movie is thought to belong to a certain genre, though, an audience develops a set of expectations of that film, whether consciously or otherwise. We anticipate that it will adhere to certain conventions. For example, if it is a western, we know that it will most likely feature cowboys and open plains, because these are some of the conventions of this genre. If it is a science-fiction movie, it may have elements of outer space and/or a futuristic setting. If it is a comedy, then it probably features elements of incongruity and exaggeration, and it is fundamentally designed to make its audience laugh. Basically, genre is a way of setting up audience expectations by delivering them with certain conventions from which the film can then build upon. It refers to both form and content.

Satire, as we read about last week, is a specific sub-genre of comedy. It is subversive and it risks being offensive, and it is always, on some level, political. As King notes, satire "offers a way of tackling serious social-political material without slipping into over-insistent and 'preachy' realms of melodrama or straight propaganda" (107). He also says that, "In some cases, however, comedy of a satirical variety may be the only way in which internal social or political criticism can reach an audience" (94). If you'd like to see an example of satire in action, I encourage you to watch this clip of Steven Colbert at the 2006 White House Correspondents Dinner.

They say his testicles grew three sizes that day.

Satire is not safe. For this reason, film producers tend to stay away from it. King talks about how satires usually only get made if they are independently produced or if the content is watered down enough to make them appear harmless. He argues that, "Absurd broad comedy and caricature dilute the satirical impact but also help to enable films such as this to gain finance, distribution and a broader audience than would otherwise be the case. The precise boundary of the substantially satirical is not easy to identify, but it might be suggested by a darker and/or sharper edge in the overall mix" (105). In other words, sometimes elements of satire are interwoven within other, more innocuous forms of comedy and/or hidden in the subtext, but you can usually pick out the satire because it contains an element of sharp social criticism.

All three of last week's movies satirized U.S. politics. Being There offered a satire of "Washington outsiders" at a time when our political system seemed broken; Election was, in many ways, a satire of political corruption in our two-party system; and Wag the Dog offered commentary on the ways in which politicians manipulate the public through mass media. These films could also be thought of as being part of a sub-genre of political comedies, as they all adhere to similar conventions (i.e. they are about American politics, they offer commentary on real-life events through satire, they maintain an aloofness that prevents us from taking them too seriously, etc.).

In a similar respect, all of this week's films are parodies. They are: Hot Fuzz, I'm Gonna Git You Sucka, and Airplane! As you will read about this week, parody differs from satire in some pretty significant ways. Whereas satire offers political or social commentary, parody is a deconstruction of aesthetics. A parody film exposes the conventions of a genre, leaving them open to ridicule. It may also poke fun at a specific work, whether film or otherwise. A parody can contain elements of satire, but it is not a requisite. As I will discuss in more depth next week, parodies have been around for nearly as long as motion pictures have existed, and they essentially serve as inside jokes with their audiences. It can also be argued that parodies prevent film form and content from becoming too predictable because they point out cinematic conventions that have become clichés and should probably be retired.

As you're watching this week's movies, I want you to think about the genres and/or specific films that they are deconstructing. Depending on your familiarity with these types of movies, this may require some additional outside research. Once you have watched at least one of them and read this week's blog posts for context, as well as the assigned reading (King chapter three, second half: pg 107-138), please respond to the following screening question prompt:

Cite at least three examples from this week's film(s) that called attention to specific genre conventions for comedic effect. Describe the scenes, discuss how the jokes played out, and incorporate references to this week's reading.

The following students are exempt from this week's screening question, as they are assigned blog posts:

Michael Abels - Review of Reviews (The Player)

Cynthia Baber - Review of Reviews (After the Fox)

Katrina Bertz - Biography (Neil Simon)

Jenna Schultz - Biography (Peter Sellers)

Terry Snider - Biography (Vittorio De Sica)

Kristen St. John - Biography (Robert Altman)

Alexa Stanford - Review of Reviews (Be Kind, Rewind)

I think you will enjoy this week's films. As always, you are encouraged to watch all of them. Email me with any questions.

No comments:

Post a Comment