I don't know why this keeps happening. It's like the title is cursed or something.

|

| Benign incongruity between expectations and reality = funny. |

And now, I shall do the opposite of funny and explain the basic mechanics of my joke. The first sentence sets it up and emotionally engages the audience, the second sentence complicates the scenario and establishes a pattern between the first two parts, and then the third sentence takes the joke in an unexpected direction that only makes sense in retrospect. Just like a knock, knock joke.

In fact, jokes typically follow the same three-act structure as just about any other form of narrative. This stuff goes back to Aristotle, who explained it as 1.) thesis, 2.) antithesis, and 3.) synthesis. Part one is the set-up, part two is the complication and part three is the resolution.

In reference to last week's lecture, in most American movies, the thematic question is posed in act one (the first 20-30 minutes or so), it is then tested in an attempt to disprove it in act two (the 60 minutes in the middle, which forms the bulk of the story), and the theme is then validated in act three (the last 20-30 minutes).

To look at it another way, for those of you who are more interested in science than literary theory, you can think of this much like the scientific method. First you state your hypothesis, then you perform experiments that are fundamentally designed to disprove your theory (because if the experiments are designed to prove the theory, they almost certainly will), and then, ideally, the hypothesis is validated, but it has usually been revised somewhat to reflect that which was learned through experimentation. This is the process through which both scientists and writers create and disseminate knowledge. It is also how comedians typically structure jokes. One, two, three...

Consider Misch's joke from the first page of the book:

Guy goes to a doctor, doctor says, "You're gonna die."

Guy says, "Oh my god! How long do I have?"

"Ten."

"Ten what?! Weeks? Months?"

"Nine... Eight..."

In the set-up of the joke, we become emotionally engaged in the story. The doctor just told a man that he is going to die (and, of course, mortality is a common source of anxiety among human beings). So now we care what happens next.

Then it gets complicated further. He's going to die in ten something, months possibly weeks.

But then with the punchline, we enter the realm of the absurd, where the doctor is counting down the seconds until the man dies. The initial emotional investment in this character is then detached from our intellectual understanding of the joke and expressed as laughter.

The "rule of threes" applies so often in comedy because the first two parts establish a pattern, which is then disrupted by the punchline. If you want to think about in geometric terms, two points form a line, but then a third point can form an angle, thus the rendering takes on a new dimension.

Human beings are hardwired to find patterns in things. It's kind of what we do. Since early humans didn't have the physical advantages of other animals, our frontal lobes developed as a way of coping with a hostile environment. Our ancient ancestors survived by seeing patterns in the natural world and attempting to make sense out of them. As a remnant of this evolutionary process, modern humans still have a built-in reward system for when we find patterns in things. Our brains release endorphins as a way of saying, "Good job, brain. Keep up the good work." Yes, they are basically the brain's form of Scooby Snacks.

| Atari 2600 games = finding and exploiting patterns. Other than that, they don't really hold up. |

In a joke, when the pattern is suddenly disrupted by the punchline, our bodies release adrenaline as part of the "fight or flight" response. In PET scans, the brain lights up like a Christmas tree when a person is processing a joke. As the neurons fire away, the intellectual incongruity is resolved through a new understanding (i.e., getting the joke), and our brains are flooded with more of those sweet, sweet endorphins. In terms of neurochemistry, this is why it feels good to laugh.

Music has the same effect on our brains. The fundamental difference between music and noise is that music not only follows a pattern, but it also diverges from that pattern in ways that may surprise us. The steady din of a refrigerator or a ceiling fan, after all, may in fact follow a distinctive pattern, but most people would not consider these sounds to be music. On the same token, if a musician plays a single note repeatedly, then one could certainly argue that this, too, is not music. The same could be said for the collected works of Nickelback.

(In comedy, a joke like this is referred to as "low hanging fruit.")

Personal tastes notwithstanding, one of the primary reasons that we enjoy music is because it, too, offers opportunities for our brains to distinguish elements of repetition. When we recognize the underlying structure of a song, our bodies release chemicals that make us happy. But when the pattern suddenly changes in either shape or complexity — i.e. the chorus (in western music) — this causes a shift in our response. This, typically, is when the music moves us. When our brains perceive these sudden disruptions in the established pattern, just as with comedy, our bodies release adrenaline. This combination of neurotransmitters is one of the reasons why so many people throughout human history have enjoyed music; it also explains to a large extent why people tend to love comedy. Comedy, much like music, makes us feel good.

In music, dramatic tension is created through harmony and dissonance. In comedy, it is produced by juxtaposing one train of thought with another, causing an idea to effectively jump the tracks. The tension that this causes is expressed as laughter. In a narrative, this same effect is created through conflict. In a painting or a photograph, this tension is achieved through varying degrees of contrast. Even the idea of balancing flavors when cooking follows this same basic premise. Substance is achieved through difference. Contrast provides stimuli to which our brains react.

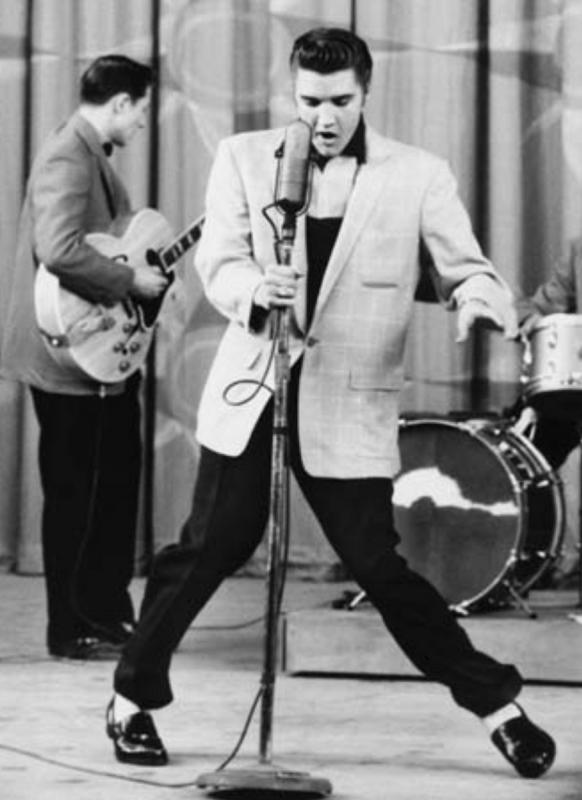

One of my kids' favorite TV programs is a hidden-camera magic show. When they watch it, their response is typically laughter, because the tricks that the magician performs disrupt their sense of reality. In fact, when any magician performs an act that we logically know is impossible, such an illusion creates an intellectual incongruity that functions exactly like a good joke, and so our response is typically laughter. It is also not uncommon to hear laughter in the audience of a horror film, even good ones (or as Misch notes, from the screaming teenage girls in the audience of Elvis's first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show). In each of these scenarios, there is a sudden disruption in one's sense of normal.

Both of the films we watched last week draw on familiar elements of our reality and then exaggerate them for comedic (and arguably political) effect. Idiocracy satirizes consumer capitalism and the "dumbing down" of American culture, while Team America: World Police pokes fun at U.S. foreign policy in a post-9/11 world. In both cases, these filmmakers call attention to things that people might not otherwise think about, even though the implications in both cases are pretty severe. If either of these filmmakers had chosen to make documentary films that explore these same ideas, the effects would be quite different and more people would probably feel insulted and/or alienated by their contentions. With comedy, though, they can not only address these issues without making their audiences feel like they are being lectured to, but they can also give them happy brain chemicals while doing so.

In this week's reading, Geoff King says that, "comedy tends to involve departures of a particular kind -- or particular kinds -- from what are considered to be the 'normal' routunes of the social group in question. In order to be marked out as comic, the events represented -- or the mode of representation -- tend to be different in characteristic ways from what is usually expected in the non-comic world. Comedy often lies in the gap between the two, which can take different forms, including inconguity and exaggeration" (5).

A lot of comedy comes from looking at the familiar aspects of everyday life and either decontextualizing these elements or exaggerating them. Incongruity can readily be seen in any "fish out of water" movie, where a character is placed in an unfamiliar context and much of the humor is typically drawn from specific differences between the culture and the individual. Examples from films that we will watch this semester include: Being There, Borat, Blazing Saddles and The Jerk; but incongruity is also the "sleight of hand" used in any joke where the audience is set up for one thing and then presented with something else. Similarly, exaggeration is used in just about any comedy; part of what makes it funny is the difference between reality and its comedic presentation. If we were to believe that the world contained within a comedy film was real, we might be less inclined to laugh at it, but by presenting an exaggerated version of reality, the audience is allowed an emotional distance from the characters on screen. However, by also having characteristics with which an audience can also empathise, these characters engage the viewer in their dramatic plights.

| Scene pictured is from The Jerk, which is one of your options on week 14. |

King refers to these qualities as allegiance and alignment, but you could also say that it basically comes down to sympathy and empathy, respectively (although it is a sympathy that typically maintains a certain emotional detatchment). In my opinion, the most important question any filmmaker can ask is, "Does the audience care what happens next?" This is just as true with comedies as it is with any other kinds of film. As King quotes film critic Raymond Durgnat: "There can be no jokes without a dramatic undertow, for there can be no incongruities if there is no emotional tension."

King later adds, "Film comedy, like all popular cultural products, is rooted to a large extent in the societies in which it is produced and consumed." Excluding only the purely absurd, I would agree that comedy typically draws from a common reality. This is why the jokes in Romanian made no sense to me. King continues, "The norms from which departures are dramatized in comedy are defined to a large extent at the social-cultural level. Such acts of comic departure can provide revealing insights into the underlying and often taken for granted assumptions of the society in question" (17).

Through film comedies, we can understand how 'normal' has been defined at various points in our history, as well as how this definition has been challenged.

When you are watching this week's films, I want you to think about the realities that they reflect in terms of their social and historical contexts. How are incongruity and exaggeration used to draw humor from these realities? Who or what are the targets of their jokes? Keep all of these factors in mind when you think about this week's screening question:

How did [the film you chose to watch] attempt to subvert societal norms?

As always, you should cite specific examples from the film and include quotes from this week's reading (King Chapter 1 - first half, pg. 19-50). I also highly recommend that you first read this week's student blog posts for context.

The following students are exempt from answering this week's screening question, as they are assigned blog posts:

Josh Gomez (Review of reviews: The Yes Men)

Cory Jackson (Review of reviews: Where in the World is Osama Bin Laden?)

Michael Placente (Biography: Morgan Spurlock)

All students are encouraged to comment on blog pages. For anything not directly related to the lecture, there is even a class discussions page. Use it. The more you put into this class, the more everyone will get out of it.

Enjoy this week's films. They are She Done Him Wrong, Modern Times or Duck Soup. These are all older movies, so if some of the humor seems lost on you, it's probably best to keep in mind that you were not the target audience. That said, in order to properly contextualize these films, you should be thinking about who the target audience might have been.

No comments:

Post a Comment